Navigating the Ocean of LLM (Pre-)Training Data

My journey with large-scale LLM (pre-)training data: search (infini-gram), tracing LLM outputs (OLMoTrace), and some recent explorations.

N-gram search in massive text corpora

Modern LLMs are pretrained on massive text corpora with many trillions of tokens. While we don’t have access to the training data of the most frontier ones, several openly-released datasets (e.g., Dolma, DCLM, FineWeb) give us some proxy. Problem is, if you dump a dozen-terabyte dataset on HuggingFace, even if it’s “open” to everyone, it’s still hard to know what is in the dataset. (The HF dataset search function doesn’t work for such huge datasets, as you may have expected.) The ability to search is crucial but absent.

This was the problem Alisa and I ran into when we were working on memorization traps for LLMs. The original idea was, larger LLMs are more persistent at completing well-known phrases with the common ending word (e.g., completing the proverb “What everybody says must be” with “true”), even when instructed otherwise (e.g., “Write a sentence about challenging common beliefs”). I was curious if the phrase’s frequency in the LLM’s training data is correlated with such persistence. But this needs me to count n-grams in a huge corpus, and there wasn’t a handy tool for this.

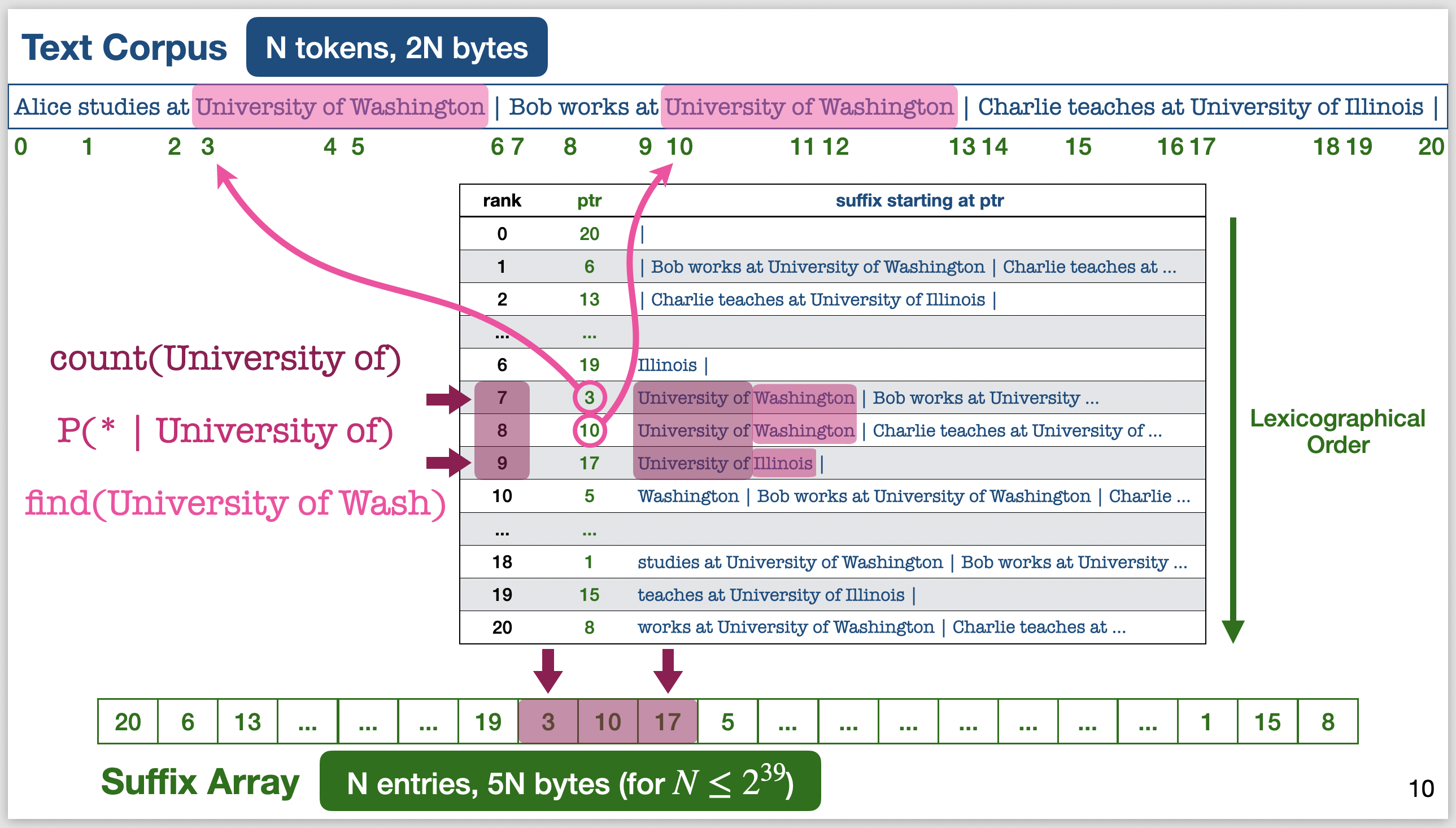

With my competitive programming background, I immediately recognized that this can be efficiently solved with a suffix array (SA). The main difference is scale – in CP we build SAs for up to $10^6$ elements, but now we need to deal with $10^{12}$ elements. This means we need to parallelize the SA index building, and we can’t keep all things in RAM simultaneously.

Illustration of the suffix array, on a toy example with about 20 elements.

Illustration of the suffix array, on a toy example with about 20 elements.

At the time there were parallelized implementations of SA floating around, the most prominent being the Rust library written by Lee et al for text deduplication. Many work, including mine, adapt their code for SA indexing (albeit a few bugs and inefficiencies which I fixed while learning to read Rust), and I really appreciate their awesome release.

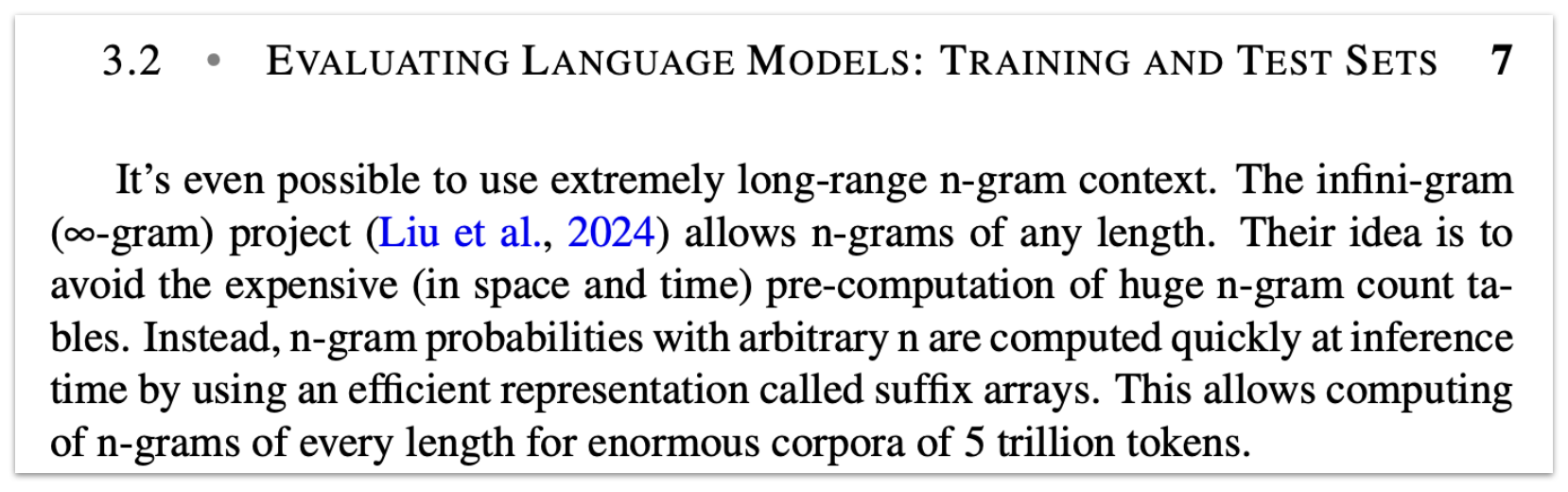

With the SA built for corpora like the Pile, we had some findings on memorization, but not interesting enough to put together a paper. This thing sat on my servers for a few months, then one day I chatted with Sewon about this and we decided, “let’s use this to build the biggest n-gram LM ever and see what happens!” Not only did we achieve the biggest in terms of reference data (5 trillion tokens, beating previous record set by Jeff Dean’s team at Google), but we also support arbitrarily large context length $n$ – hence its name infini-gram. This turned out to be the story we wrote in our COLM paper, which got mentioned in the 2024 edition of Jurafsky & Martin’s NLP textbook as a modernization of n-gram models.

Infini-gram mentioned in the Speech and Language Processing textbook.

Infini-gram mentioned in the Speech and Language Processing textbook.

I visioned this beyond being a paper. This could be a research infrastructure, a tool accessible to everyone to search and learn about LLM training datasets. Lots of people could use some instant insights to these datasets from time to time, without the overhead of building SA and setting things up. So in addition to the regular code release, I also built a web interface and a free API endpoint. As of July 2025, the API has served over 700 million queries.

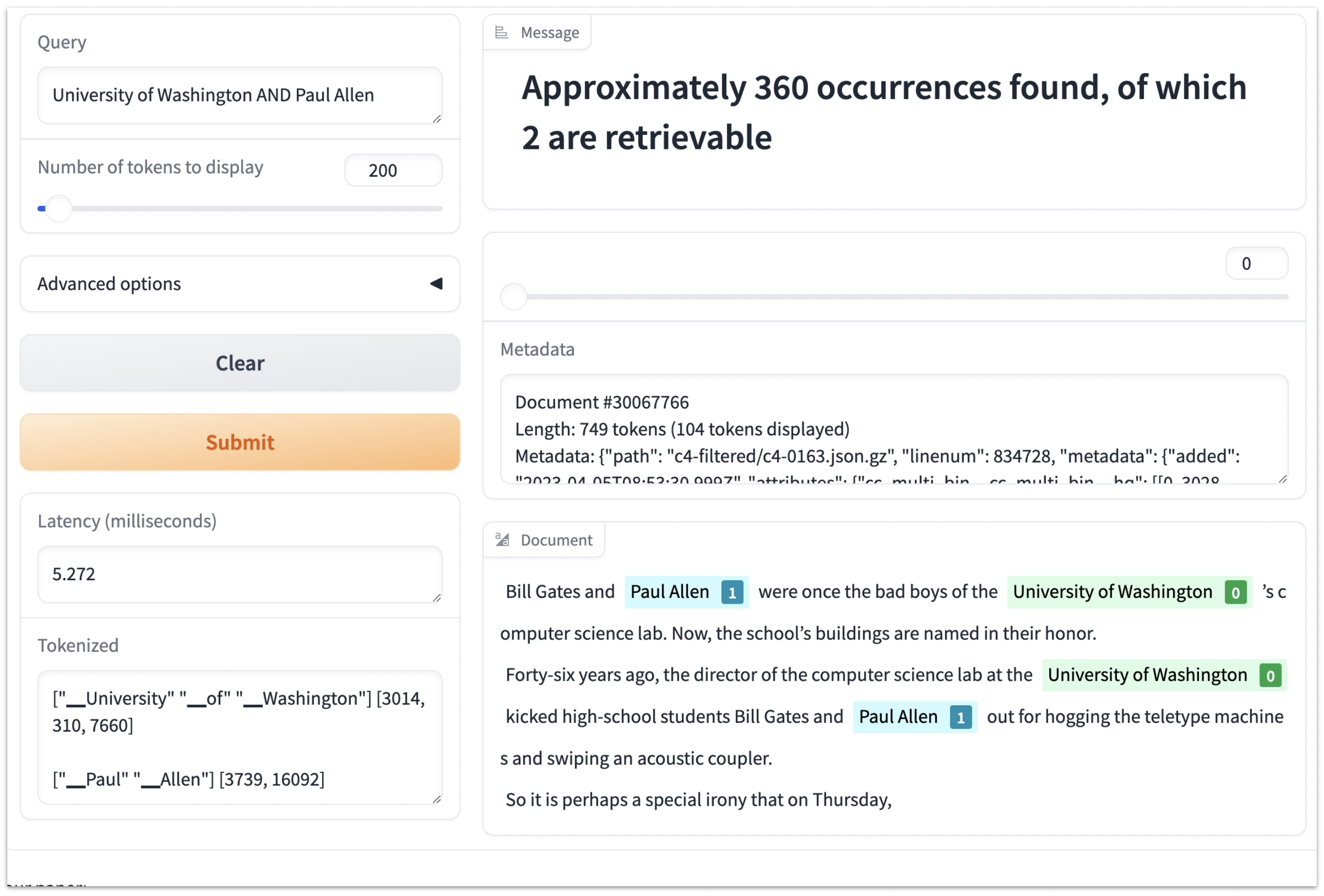

Publicly releasing a web interface came with many extra work. I wrote the original inference engine so that the SA can be used as an n-gram LM, so it had optimized functionalities like counting, computing the next-token distribution, and figuring out the maximum context length $n$. But these numbers are dull for users to look at. (Imagine Google Search only tells you how many hits there are, but not all the links and excerpts.) It’d be much cooler to show the context where the query term appears, and where the document was originally crawled from.

So I went back to tweak the data structure and aligned documents with their metadata. Folks around me also shared feedback that being able to search for co-occurrence of multiple terms would be super useful, so I invented a fast algorithm to search for CNF queries (which I even forgot to describe in the paper 😅).

A screenshot from the infini-gram web interface, showing document search with CNF queries.

A screenshot from the infini-gram web interface, showing document search with CNF queries.

Another thing is efficiency. Users won’t like to wait, so it’s crucial to decrease latency and increase throughput. Initially I wrote the inference engine in Python, but later moved to C++ to get true parallelism without having to deal with the GIL. The first version of my C++ engine communicated with the Python web server via an IPC pipe, which was quite unstable and crashed almost every day. With the help of Zihao Ye, I moved to Pybind11 to interface C++ and Python and this has been really good.

C++ also grants me finer-grained low-level I/O control to turbocharge the latency.

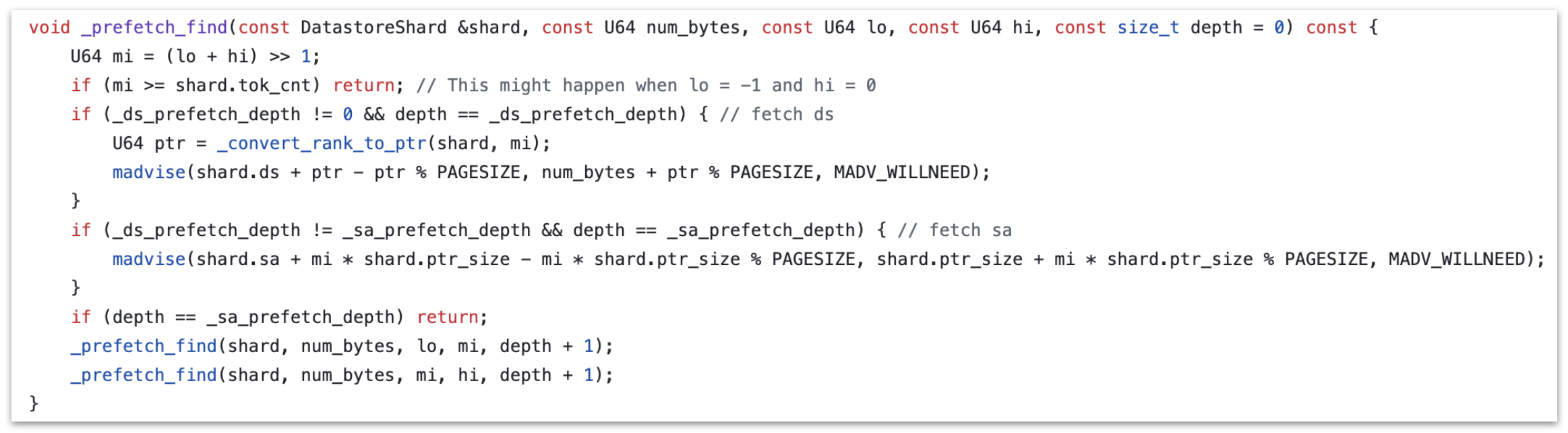

One trick is pre-fetching.

Since the SA index is too big to fit in RAM, they need to be mmap’ed from disk.

find() – the basic operation underlying all queries in infini-gram – involves a binary search on the SA, which means about $2 \log N \approx 80$ sequential, random disk reads.

(Well actually it’s 2 binary searches, but most disk reads are shared.)

However, the disk reads are not really random and there are patterns to exploit: when binary-searching over an array, at any point we can know the entries we will be looking at in the next, say, $s=3$ steps (there are $2^{s+1} - 2 = 14$ such entries).

If we pre-fetch the values of these entries, the one we really want to look at will likely be ready in RAM when we need it.

With SAs, in each step of the binary search, we don’t just compare the value in the SA entry; we need to interpret that entry as an offset in the text dataset and do string comparison with the suffix starting at that offset.

Consequently, we need to pre-fetch the suffix as well, and doing that requires us to already have the SA entry in RAM.

To solve this, I devised a two-tier pre-fetching strategy: at each binary search step, prefetch SA entries $s$ steps ahead, and prefetch the suffix $r$ steps ahead (with $r < s$).

After some tuning on the production server, I found $s = 3$ and $r = 1$ to give the lowest latency.

With the SA index stored on AWS EBS gp3 SSDs (16000 IOPS, 1000 MB/s), the average latency of the find() operation is about 20 milliseconds.

Code for pre-fetching in

Code for pre-fetching in find() operations.

Setting up the API endpoint caused even more hurdles. I used the AWS API Gateway to handle rate limits and malicious traffic, but it wasn’t easy to correctly chain up all the components like instances, target groups, network load balancers, security groups, API resources, VPCs, and custom domain names. The API is for batch processing, so it needs to prioritize throughput over latency. Pre-fetching reduces latency at the cost of burning more disk I/O operations, and at high traffic the disk IOPS (I/O ops per second) becomes the bottleneck (I’ll cover this in detail in the OLMoTrace project below), which means I had to turn off pre-fetching for API queries.

As my API starts getting more traffic, more problems surfaced. One thing I noticed was that my instance would OOM and go down every few days, and the devil turned out to be the page table. Mmap’ing the index from disk doesn’t come for free: for every 4K block on disk, a page table entry (8-byte integer) has to live in RAM. By default, mmap uses a lazy strategy to populate this page table on demand, but as more disk blocks get accessed, the page table grows and there’s no apparent way to evict it from RAM. Eventually, I had to allocate an instance with bigger RAM so that the entire page table can fit.

I want to say there are lots of grunt work that I didn’t write about, such as designing a easily-usable API interface, managing versioning between different components, etc. Overall, I’m really glad that I flashed out all those systems and learning a lot in this journey, and I want to express my deep gratitute to my advisors for kindly offering the cloud credits to let me keep the service running.

Connecting LLM outputs to their training data

Infini-gram was a splash, but to use it you need to clearly know what to search for. At the same time, why LLMs generate the outputs they do was still largely a mystery, and it was intertwined with discussions on copyright and AI creativity. Can infini-gram contribute to this challenge by directly connecting LLM outputs to their training data?

If we can find long pieces of LLM outputs that have appeared verbatim in its training data, in many cases it is pretty good insight that the LLM may have learned such token sequences from these training documents alike. This can be a “data tracing” tool that complements things like influence functions (which is not scalable) and mech interp. I was messing around with this idea in mid 2024, and eventually I joined efforts with Ai2 to build this tool, OLMoTrace.

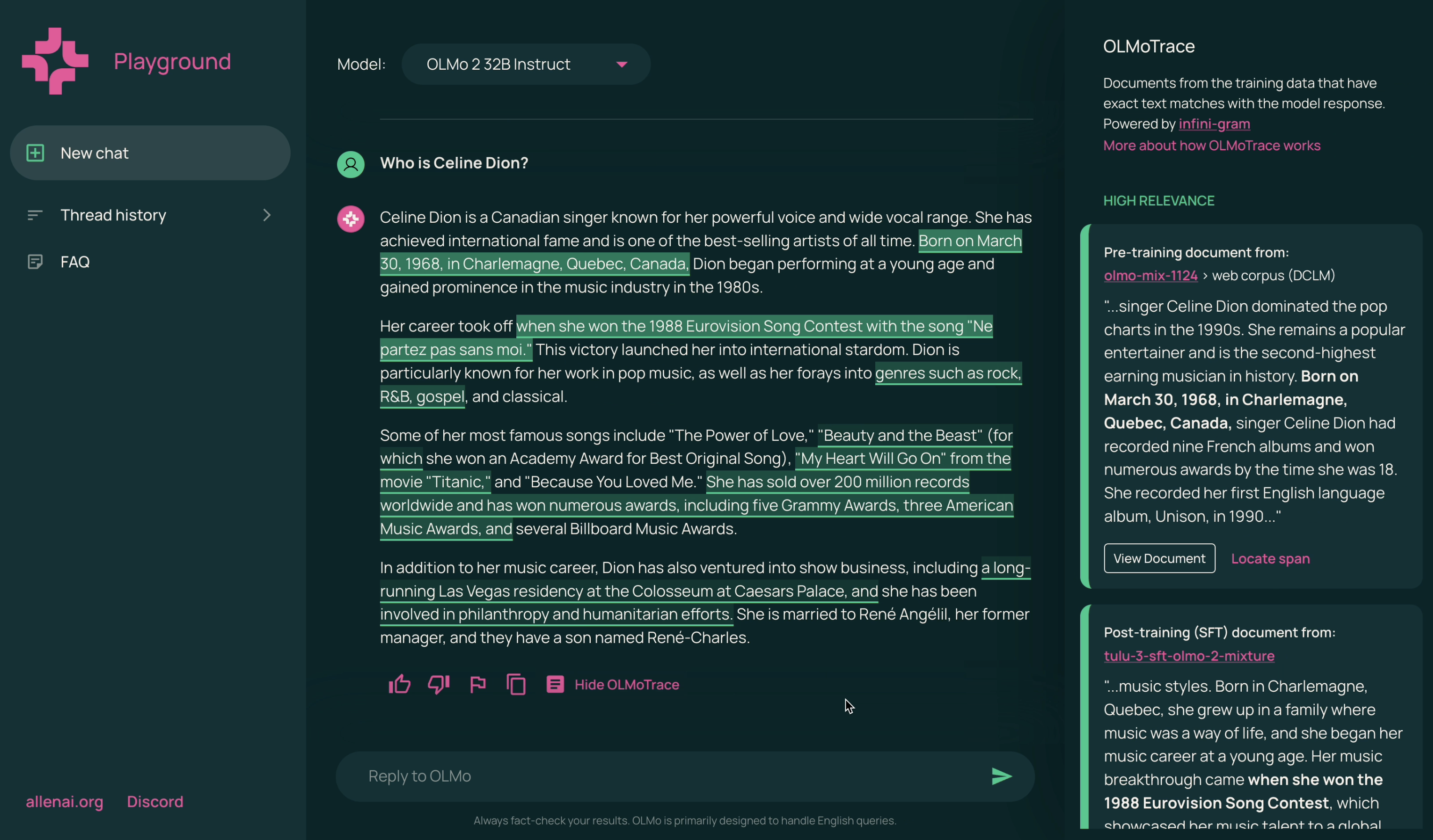

A screenshot of OLMoTrace. Highlighted spans in the model response appear verbatim in the model’s training data.

A screenshot of OLMoTrace. Highlighted spans in the model response appear verbatim in the model’s training data.

The techincal part

Apparently, we can’t expect a multi-hundred-token LLM output to exist contiguously in the training data (unless it’s regurgitating some well-known stuff), so we should look for substrings (i.e., spans of tokens) of the LLM output that do exist. Since the training data is so huge, we can actually find a lot of long spans (e.g., 10 tokens or more) with a match. But say the LLM output has $L$ tokens, do we enumerate all $O(L^2)$ spans and query infini-gram?

Well, we could parallelize these queries, but we’ll hit the IOPS limit of disks.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation: Each find() is 80 disk reads, and we need to multiply by 12 because the data is so huge that we need to shard the SA 12 ways; each LLM output is about 450 tokens; this gives us $80 \times 12 \times (450^2 / 2) = 97M$ disk IOs.

The standard SSD on GCP has 80k IOPS, so processing each LLM output would take 20 minutes.

This is unacceptable.

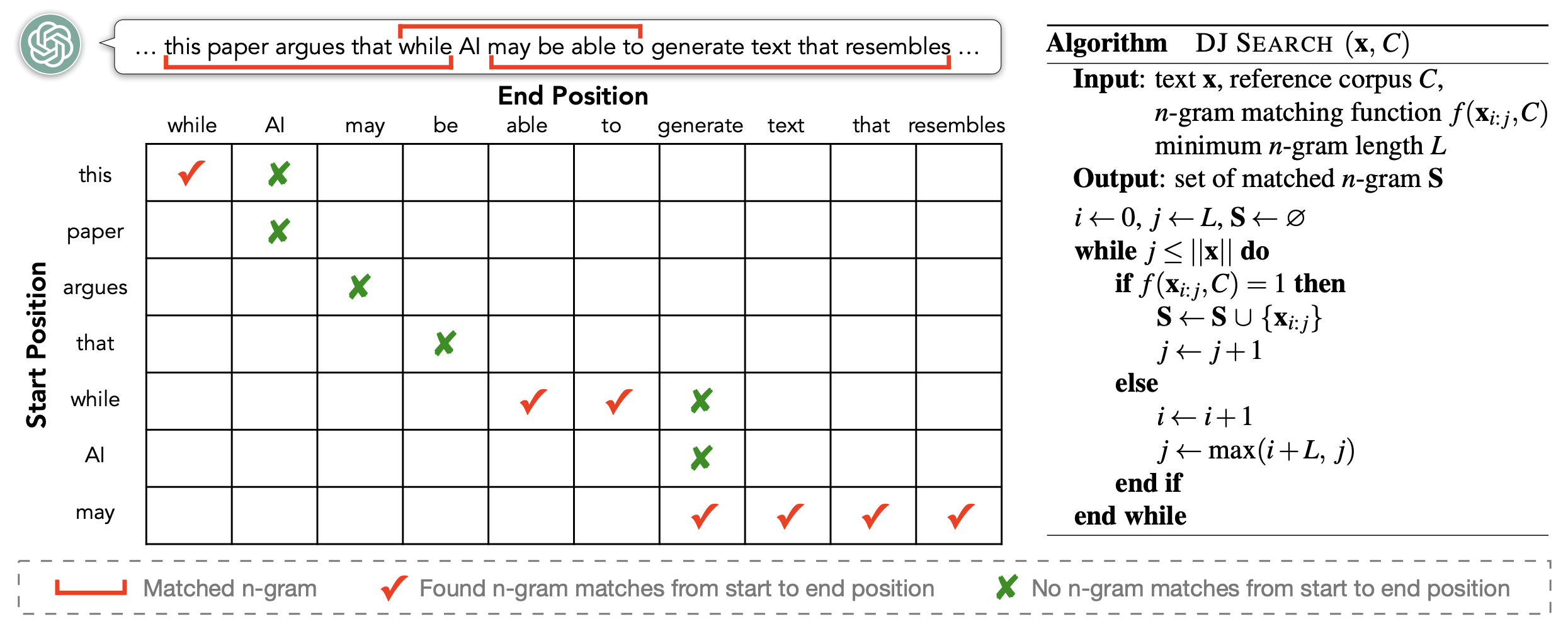

There’s an obvious monotonicity: If we already know a shorter span doesn’t exist, we don’t need to check the longer spans enclosing it. We adopted this heuristic when using infini-gram to compute the Creativity Index of text, which we define based on n-gram novelty. The algorithm, which we dubbed as “DJ Search”, reduces the queries from $L^2 / 2$ to $2L$ sequential ones, and considering each query being 20ms this gives us $(2 \times 450) \times 20 \text{ms} = 18$ seconds per LLM output. It was good enough for running research experiments offline.

A sketch of the DJ Search algo. Each marked cell represents a query to infini-gram.

A sketch of the DJ Search algo. Each marked cell represents a query to infini-gram.

But it wasn’t good enough for real-time serving.

I want this to be part of a LLM chat inferface, and the match results should pop up right after the LLM finishes generation.

The problem with DJ Search is that the queries need to be made sequentially, stacking up the latency.

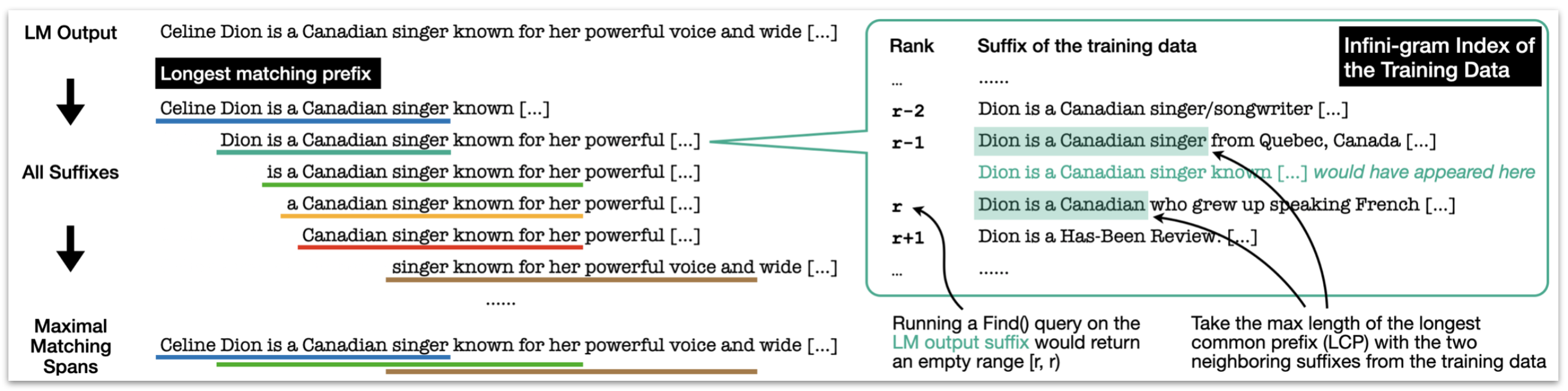

So for OLMoTrace I came up with a new smart algo that reduced to $L$ queries that can be parallelized.

The key idea is that we only need to find the “maximal matching spans” in the LLM output that exist in the training data, which can be reduced to making one find() query per suffix of the LLM output.

Interested readers can dig into our paper for details.

The final latency landed at 4.5 seconds per LLM output.

A sketch of the fast algorithm for finding “maximal matching spans” in OLMoTrace.

A sketch of the fast algorithm for finding “maximal matching spans” in OLMoTrace.

Side note: As we scale up the parallelism, we hit another limit – the number of threads that can be created in the Linux system. By default, most machines give us 1 million threads per process, which is pretty generous, but when running OLMoTrace we actually need to watch out for this. It seems that whenever we scale things up a magnitude, some unexpected bottleneck may emerge 🙃

The product part

Actually, by mid 2024 I’ve already flashed out the core technical part of OLMoTrace. But we didn’t release until April 2025, and this was mainly because we’ve been polishing it as a product. We want to make OLMoTrace a user-friendly tool that enhances LLM transparency, and that came with lots of considerations.

First thing was to reduce confusion for users. N-gram matching doesn’t account for semantics, and thus sometimes the context where the matched spans appear in the training data can be irrelevant to the LLM output. For example, if the LLM says “Celine Dion has been involved in philanthropy”, we may find “has been involved in philanthropy” in the training data but for describing another person. If a user sees this training document on the top, they may get the wrong message from our tool. To address this, we applied a reranker to surface the most relevant matched training documents in the UI. We found a BM25 reranker to be roughly as good as neural embedding models in terms of perceived relevance (via human evaluation), so we went with BM25 to avoid needing GPU machines in the production system.

We also decluttered the UI so as to not overwhelm users. There can be many “maximal matching spans” to show, some of which overlapping, which would be both challenging and confusing to highlight. We filtered the spans to only keep relatively long and unique ones (which are more likely to be worth inspecting), and did some merging of overlapping spans. We enforced spans to not start/end in the middle of a word or cross sentence/paragraph boundaries, because they look weird. We deduplicated the matched training documents, which would have spammed the UI.

We went through several rounds of bug bashes with the AllenNLP team. To integrate into a chat interface, there are numerous things we need to consider. What if there are multiple turns in the chat? What if there are contents rendered as code block / latex / markdown? What if there are Unicode characters? These are just a sample of things we had to nail down before release. We also ran an internal red teaming to understand and mitigate legal risks, including copyrighted books, lyrics, and toxic content.

Gradually I came to realize, to ship a great product, we’ve come a long way grinding numerous small aspects so that it finally meets the bar. It is very different from research.

The teamwork part

OLMoTrace is a huge team effort. For me, it’s been a unique experience to be the “tech lead” of a big team, cross-functioning across and bring together partners from engineering, research, design, comms, legal, and company leadership.

Working as a team means I need to forego my bad research-y coding habits, and instead write unit tests, lint my code, create and review PRs, etc. We also use project trackers and meet weekly to prioritize tickets.

During the few months, some people resigns and some new people join – we had a complete rotation of designers, and our PM was also assigned back-and-forth – and I had to navigate that. I also grew to be more aware of people’s individual career goals and what they wish to get from the project: someone may want to become a lead engineer; someone may want to build up as a senior research advisor; the design team may want to make an impact by unifying stuff under the new company brand. I spent some effort to align these with their role on the project and thus motivate the team.

One big part was to keep sync’ing with stakeholders and reconciling the many, sometimes conflicting, feedback. Most of the feedback were great and we incorporated them. I also had my vision of the project, and for those feedback that doesn’t go well with that vision, I would try to convince people. Of course, I also get convinced or compromise from time to time.

An interesting lesson I learned was how to communicate with leadership. Basically I need to be more prepared and less unhinged than chatting with my PhD advisors. Leadership is like your first user: they’re busy, they make a judgment based on first impression, and it’s easy for them to get the wrong message. Sometimes it means the opening sentence sets the stage of whether they’ll get it or not. Cutting straight to a demo may preempt the convo from going to a direction I don’t like. Sometimes it means having to asking them to look at somewhat cherry-picked examples before we iron out use cases more broadly.

Compress more, index more

Concurrently to OLMoTrace, I’ve been thinking how we can make even larger text corpora searchable, and in particular, Common Crawl. As the source corpus for most pretraining datasets (if not all), Common Crawl contains about 1 PB of text and continues to grow every month. If we index this corpus, we’d be able to understand (a large part of) the pre-training data of most LLMs, including proprietary ones. However, storing the SA index (on cloud) alone would cost $560k per month. Well, we’re not Google, and we need to stay with a reasonable budget.

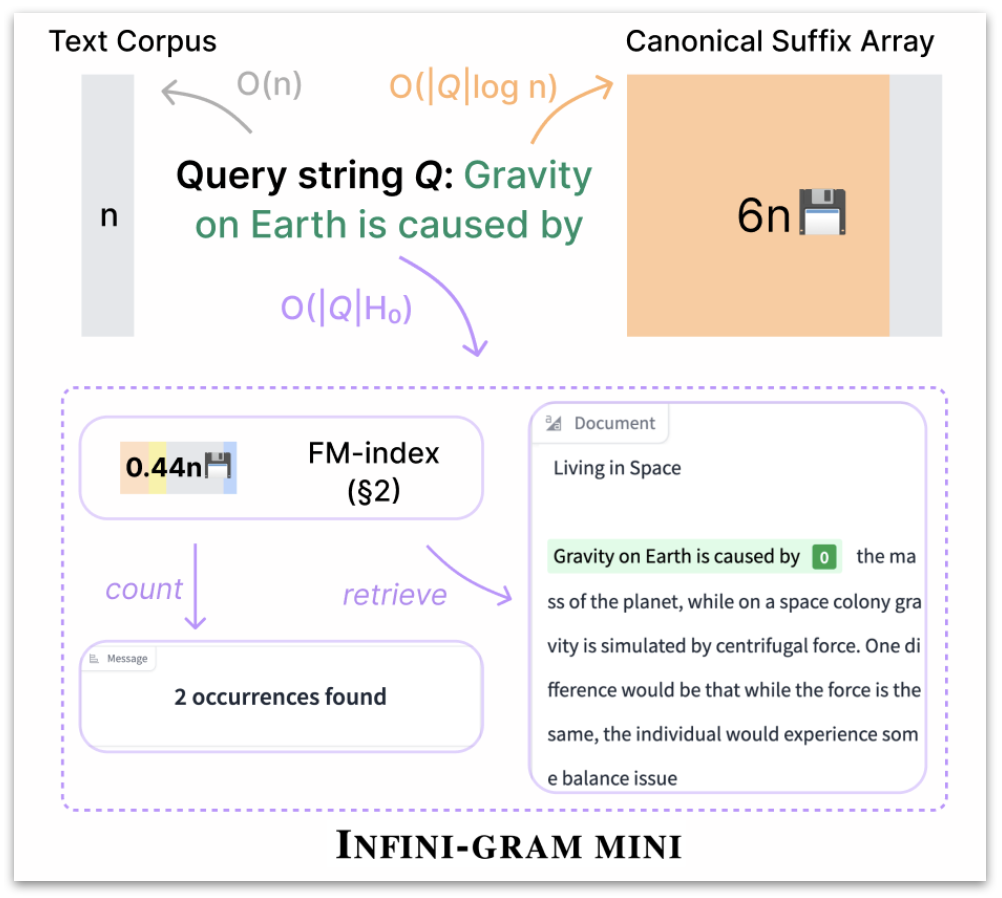

I had a call with Christina Boucher from U Florida last year and she introduced me to a data structure called FM-index. It is a compressed version of the SA index: instead of storing the full text corpus and its suffix array, FM-index store a subsampled version of the suffix array and a compressed version of some permutation of the text corpus (called the BWT). This gives tremendous storage save – up to 27x compared to SA.

Infini-gram mini uses FM-index, a more storage-efficient data structure that is similarly powerful as SA.

Infini-gram mini uses FM-index, a more storage-efficient data structure that is similarly powerful as SA.

The best existing implementation of FM-index was SDSL from a decade ago. It has only been tested on datasets beyond a hundred GB large, doesn’t have multi-CPU parallel indexing, and no on-disk inference. Working with Hao Xu, an undergrad student at UW, we did extensive engineering to overcome these bottlenecks. Our system, infini-gram mini, speeds up indexing by 18x and reduces RAM use by 3.2x compared to SDSL. With the lower storage multiplier, we can now index bigger corpora. In total, we indexed 46TB of text, including the first 3 months of Common Crawl from 2025. (Similar to infini-gram, there’s web interface and API for querying these corpora.) Indexing the entire Common Crawl is also within reach – if you’d like to sponsor this effort, please shoot me an email and I’d love to burn some of your cloud credits 💸

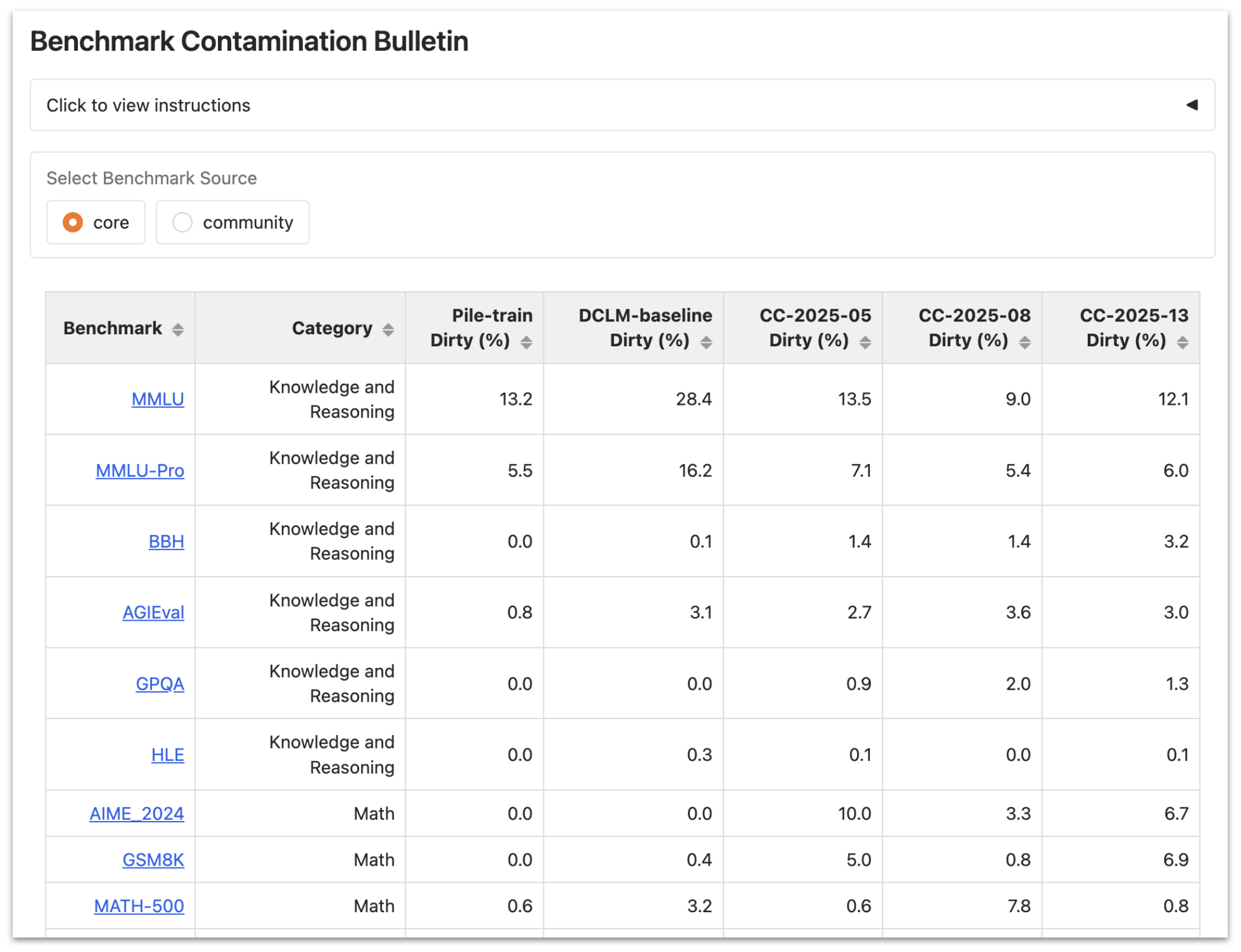

We used infini-gram mini to analyze and monitor the contamination of LLM benchmarks in Common Crawl. We found heavy contamination of widely-used benchmarks like MMLU and SQuAD. Math and coding benchmarks are relatively clean, but current practices in benchmark publishing and data crawling almost guarantee that they will get increasingly contaminated. We created a public bulletin to monitor this situation over time as more crawls are made available.

The bulletin is updated monthly with new crawls from Common Crawl, and anyone can submit new benchmarks to be monitored.

The bulletin is updated monthly with new crawls from Common Crawl, and anyone can submit new benchmarks to be monitored.

Open-source scalable deduplication

SA was used by Lee et al to deduplicate text corpora, an important step in curating pretraining data since Internet crawls contain heavy duplication. Because of my experience with SA, I took on the job of deduplication for developing OLMo 3.

We want to curate a SOTA pretraining dataset, but Lee et al’s tool has a few deficiencies: (1) for duplicated substrings, it removes all its appearances, but we want to keep one; (2) it doesn’t support “fuzzy removing”, i.e., if two nearby strings are removed, then we also want to remove the short piece between them; (3) it is still a bit slow to run for a scale like 10T tokens. To address these issues, I made some modifications to infini-gram and released this deduplication tool, bsade.

I’d like to focus on the efficiency part.

To use SA for marking duplicated text, we make a sequential pass over the SA, and for each neighboring pair of suffixes, find out if their first $k$ characters are identical.

The slowest step in SA building is a merge() step – merging several small SAs into a big SA and write back to disk – and it’s particularly slow when the text corpus contains a lot of duplicates.

The key observation is that this merge() can be combined with the sequential SA pass.

By doing so, we can (1) avoid writing back the big SA to disk, and (2) restrict the length of comparison in merge() to $k$ characters, which would speed things up if $k$ is small enough to fit into a disk block.

After looking at some real data, I found $k = 500$ characters to be a sweet spot.

With this parameter setting, I removed 14% of Common Crawl (note that I started with a dataset that’s already deduped with exact match), reducing a 10T token dataset into a 8.5T token one.

An overarching process in this project is to continually identify the most time-consuming bottleneck and optimize it (usually via parallelization). Once you optimize one bottleneck component, another component may become the bottleneck, and it goes on and on. But in aggregate, I was able to take the runtime of a single job from 2 days down to 4 hours, which made the dedup of 10T tokens finish in one day and saved lots of cloud compute money.

Combining neural LLMs with n-gram models?

Lastly, I want to share an idea that I think is very cool but didn’t get to fully flash out. The idea is to improve neural LLMs by combining them with n-gram LMs.

In the infini-gram paper, I showed that a simple interpolation of n-gram and neural LLMs can be a lot better than the neural LLM itself, in terms of language modeling perplexity. The interpolation happens in the output probability space, and I call it “late fusion”: \(P_\text{hybrid}(x_t | x_{<t}) = \lambda \cdot P_\infty(x_t | x_{<t}) + (1 - \lambda) \cdot P_\text{neural}(x_t | x_{<t})\) where $P_\infty(x_t | x_{<t})$ is the probability given by what I call an “$\infty$-gram LM”: an n-gram LM where n is dynamic for each token and takes the maximum possible context length.

But I found this hybrid model terrible at autoregressive generation. In many cases, the decoding suddenly goes off the rail into regurgitating from the training data, which can often be topically incoherent to the context. I suspected this is because the $\infty$-gram LM is accurate but over-confident: its predictions of the next-token distribution is usually very sparse (in many cases, one-hot), and even with interpolation, the distribution is undesirebly spiky.

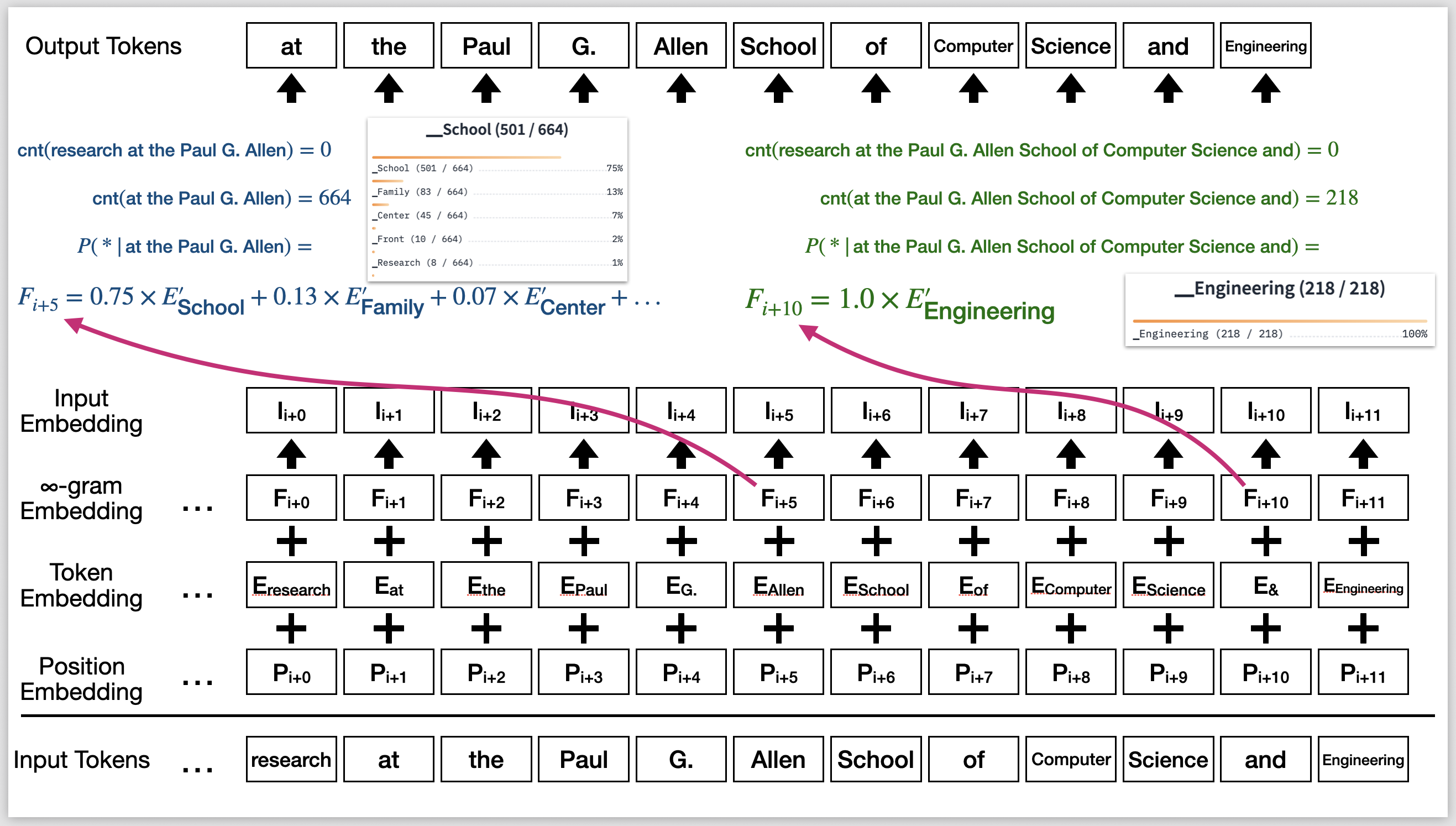

This makes me want to do “early fusion”: injecting the $\infty$-gram LM’s prediction as a “hint” to the neural LLM. The intuition is, n-gram LMs encode lots of long-tail knowledge, and hinting neural LLMs with its predictions can free the neural LLMs from having cramming all the knowledge into its parameters, which they can spare to better learn other capabilities.

More technically, we target decoder-only Transformers as the neural LLMs. At each token position, I want to inject a distribution over the vocabulary as input to the Transformer. Canonically, the Transformer’s input is the addition of two vectors: a token embedding and a position embedding. I propose to add a third embedding: the “$\infty$-gram embedding”, calculated as a mixture of token embeddings weighted by the $\infty$-gram distribution. If the distribution is one-hot, this embedding would simply be the embedding of that token. The $\infty$-gram embedding is applied at every token position. I refer to this model as infini-LLM.

Injecting $\infty$-gram LM’s predictions into the input embeddings of Transformers. In the example shown, the only reasonable choice for the last token is “_Engineering”, which is given by the $\infty$-gram LM. By injecting its embedding as input, the Transformer can decide to agree with this hint, and thus does not need to memorize the name of this entity.

Injecting $\infty$-gram LM’s predictions into the input embeddings of Transformers. In the example shown, the only reasonable choice for the last token is “_Engineering”, which is given by the $\infty$-gram LM. By injecting its embedding as input, the Transformer can decide to agree with this hint, and thus does not need to memorize the name of this entity.

Apparently, this change requires re-training the Transformer. I based my experiments on an internal version of OLMo-1B (trained between OLMo-0724 and OLMo 2). This model was pretrained on the Dolma v1.7 dataset, which I also used as the n-gram datastore. The $\infty$-gram LM inference is, well of course, powered by infini-gram.

Regularizing the $\infty$-gram LM

I wish it were that simple. There’s an obvious trap: When training the Transformer on each sequence, this sequence also appears in the n-gram datastore, which means almost all predictions made by the $\infty$-gram LM are one-hot and agree with the actual next-token. Then the Transformer wouldn’t need to learn anything, and the whole model would have zero generalization.

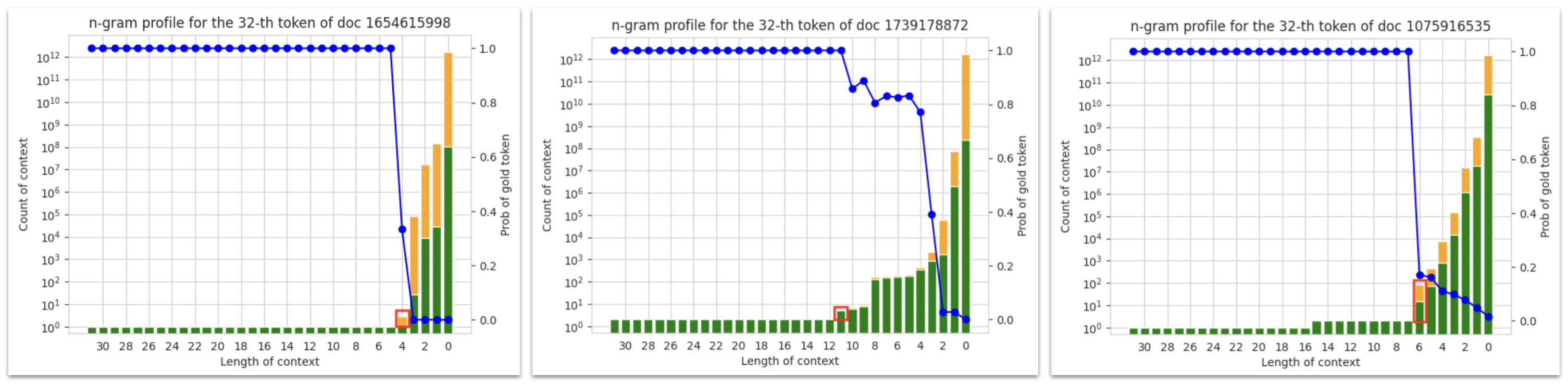

We can see this problem by plotting an “n-gram profile” for some selected token of the training sequence. Each bar represent the number of appearances of the n-gram preceding that token; the green portion is where the next-token after each appearance matches with the selected token, and orange portion is for mismatches. At small n, the count is big, but accuracy is low (which is exactly the problem with traditional 5-gram LMs). At large n, we see the count is 1 (in the left figure below), and that’s due to this training sequence appearing in the n-gram datastore.

The n-gram profile of two selected tokens. Left: the training sequence appears once in the dataset; the $\infty$-gram LM prediction is sparse and always correct. Middle: the training sequence appears more than once in the dataset (i.e. there is duplication). Right: an ambiguous case where it’s unclear what constitutes duplication.

The n-gram profile of two selected tokens. Left: the training sequence appears once in the dataset; the $\infty$-gram LM prediction is sparse and always correct. Middle: the training sequence appears more than once in the dataset (i.e. there is duplication). Right: an ambiguous case where it’s unclear what constitutes duplication.

If the training sequence only appears once in the dataset, it is easy to exclude: we can simply use the distribution indicated in the red box. Duplication further complicates things. In the middle figure above, the sequence appears more than once, and we may want to exclude all of them from the $\infty$-gram prediction. However, there are ambiguous cases like the right figure: there’s another sequence sharing a 15-gram suffix with the current training sequence, and it’s unclear whether to count this as a duplicate; if we don’t remove it, the hint given to Transformer may be too strong. I need to come up with a heuristic, and it has to be efficient to implement (discussed in the next section).

After looking at the n-gram profile of many tokens and trying a few things, I landed with the following rule: when there’s a range of values of n where the count is identical, all appearances in this range give too strong hints and should be excluded. In n-gram profiles, this can be identified as a long “plateau” where the count is constant, and these bars are excluded. The $\infty$-gram prediction is taken from the red-boxed portion shown in the above figure. Some tuning shows that the length of this plateau should be at least 5.

Training efficiency

WARNING: This section is very technical but I’m being hand-wavy here. Please feel free to skip this.

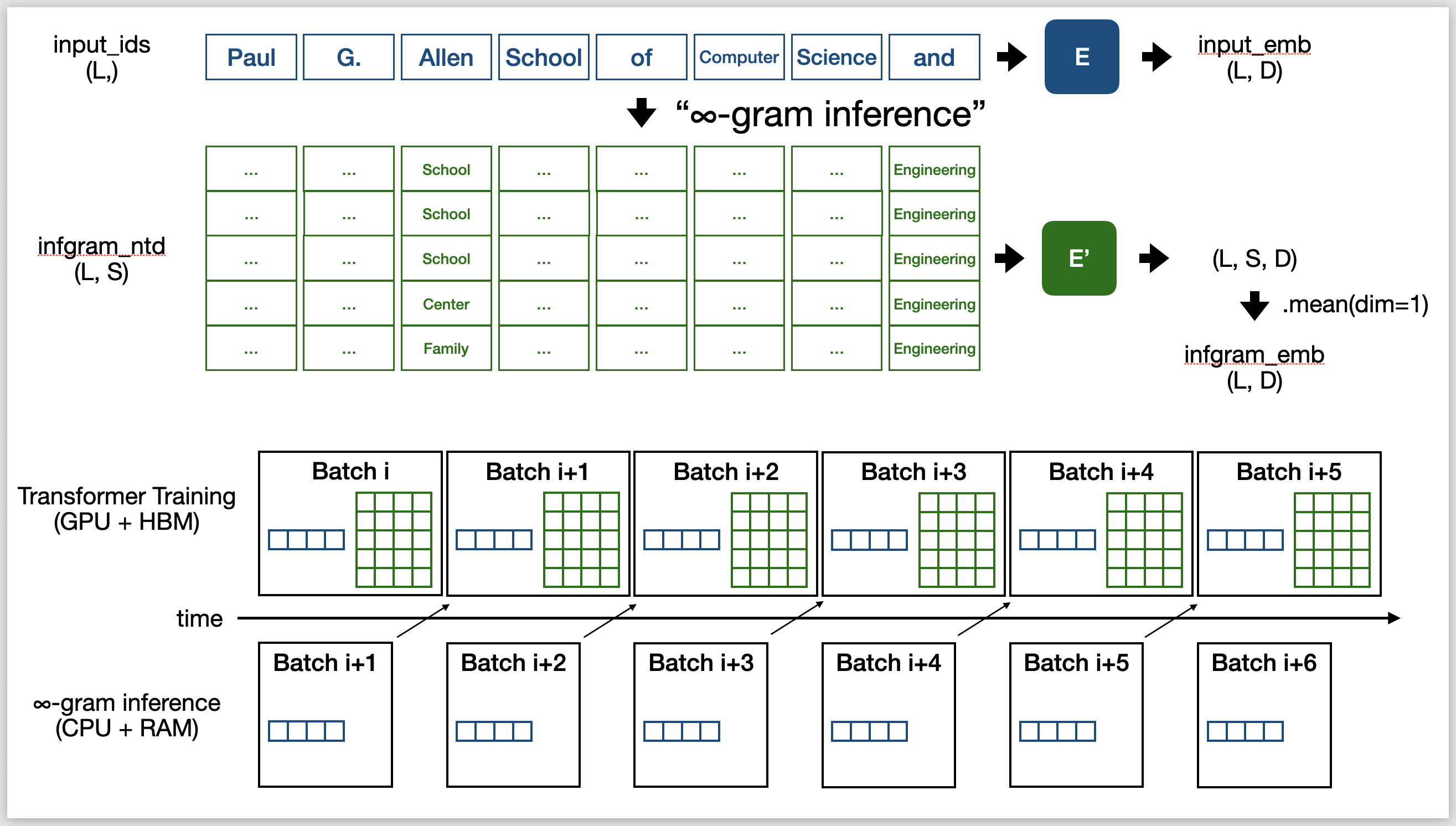

Infini-LLM adds an extra step to the model pipeline: given a training sequence, we need the $\infty$-gram prediction for every token before passing things into the Transformer. I don’t want to slow down pretraining with my stuff, otherwise the benefit would not justify the cost. Maintaining tokens-per-second (TPS) is a critical objective, and required a lot of engineering.

On 8 A100 nodes and with a batch size of 4M tokens, the OLMo-1B model roughly trains at 2 seconds per batch. Fortunately, infini-gram inference doesn’t need GPU, so I can pre-fetch the $\infty$-gram predictions for the next batch while the GPUs are training on the current batch. This allows me to parallelize, and “hide” the extra processing time behind GPU time if I can get it below 2 seconds. That said, running 4M infini-gram queries in 2 seconds is no joke, can’t be done naively.

Optimizations for getting $\infty$-gram predictions. Upper: $\infty$-gram distributions are represented with $S$ discrete samples. Lower: $\infty$-gram predictions are pre-fetched and latency is hidden behind GPU training.

Optimizations for getting $\infty$-gram predictions. Upper: $\infty$-gram distributions are represented with $S$ discrete samples. Lower: $\infty$-gram predictions are pre-fetched and latency is hidden behind GPU training.

First, the SA index cannot live on disk anymore, they need to be loaded to RAM (and good RAM with high throughput, ideally DDR5).

Luckily, GPU machines are usually generous in RAM, and LLM training mainly uses GPU HBM but not CPU RAM.

For H100 nodes each with 2TB RAM, to fit the SA index (12TB for 1.7T tokens), I shard it 8 ways and distribute the SA index across 8 nodes.

With sharding, we need to do some network communication: for the training sequences, a gather_all() operation to make them available to all nodes; for the $\infty$-gram predictions, an all_to_all() operation to aggregate the results.

Since the gloo backend (for CPU tensors) does not support all_to_all(), I instead use a series of scatter() operations to simulate it.

Next, it is extremely inefficient to represent each $\infty$-gram distribution as a 50k-dimensional vector. Instead, I leverage sparsity and approximate the distribution with up to $S$ discrete samples (typically I choose $S = 20$). This relieves network communication from being the latency bottleneck.

Lastly, I reduce the number of memory accesses in $\infty$-gram queries. I won’t elaborate the details here; on a high level, it involves leveraging some monotonicity when processing tokens from left to right in a training sequence. My regularization technique has this monotonicity property. The effect is reducing the number of memory access per token from $O(\log L \cdot \log N)$ to $O(\log N)$ amortized (where $L$ is the sequence length). Also, to make the sampling of next-token efficient in the presence of regularization, I had to the build SA index with all document strings reversed in the datastore.

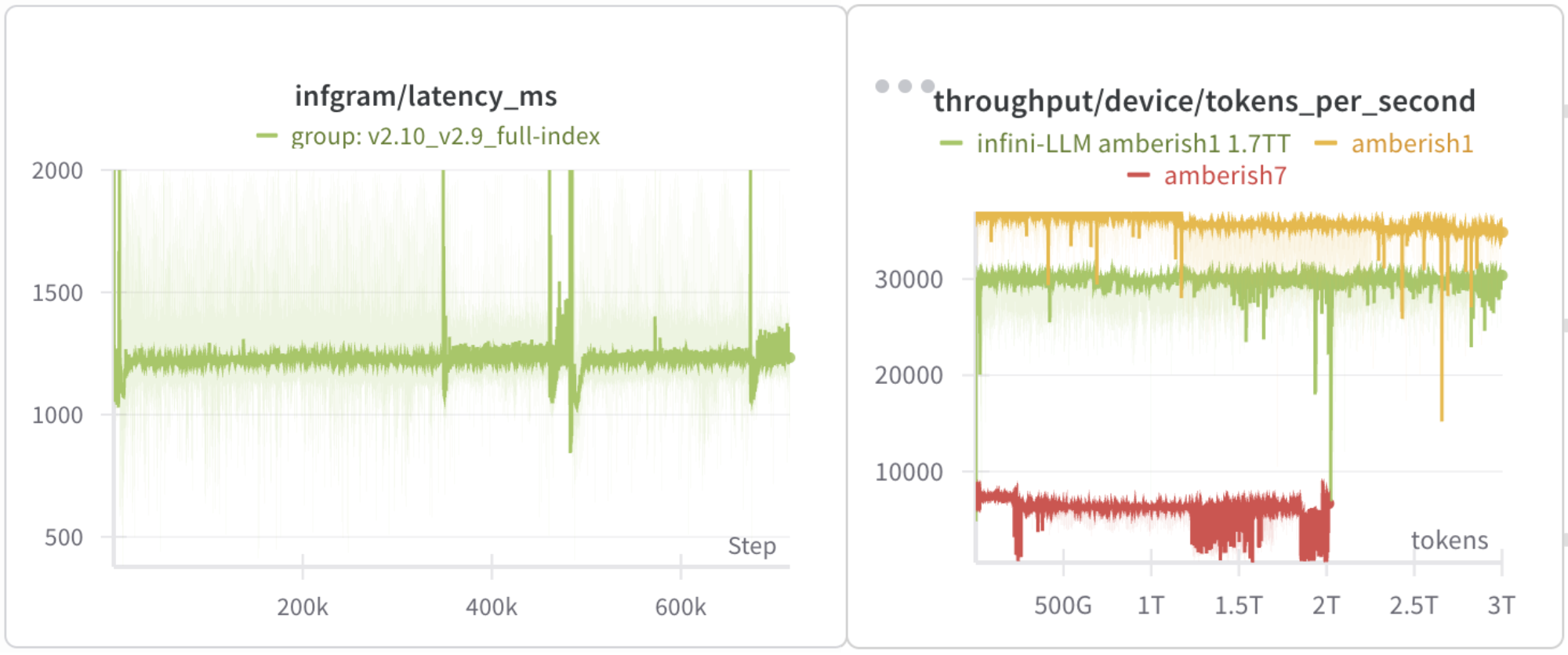

Left: the per-batch processing time for $\infty$-gram predictions, roughly at 1.2 seconds. Right: the overall training throughput; infini-LLM is almost as fast as regular Transformer pretraining.

Left: the per-batch processing time for $\infty$-gram predictions, roughly at 1.2 seconds. Right: the overall training throughput; infini-LLM is almost as fast as regular Transformer pretraining.

With all these optimizations, I was able to bring the $\infty$-gram inference latency down to 1.2 seconds per batch, which fits in the 2 second target. The actual pretraining throughput is about 30k TPS, slightly lower than the 35k TPS in training the Transformer itself. This is promising, but I think can be optimized better. I suspect the reduced TPS is due to network saturation – the $\infty$-gram inference also needs network communication and may be competing with GPU distributed training for bandwidth.

Evaluating the model

As mentioned above, I experimented with training infini-LLM based on the settings of an internal version of OLMo-1B (codename “amberish1”). The n-gram datastore is the model’s pretraining data, Dolma v1.7, which has of 1.7T tokens. All other data and training settings exactly follows amberish1.

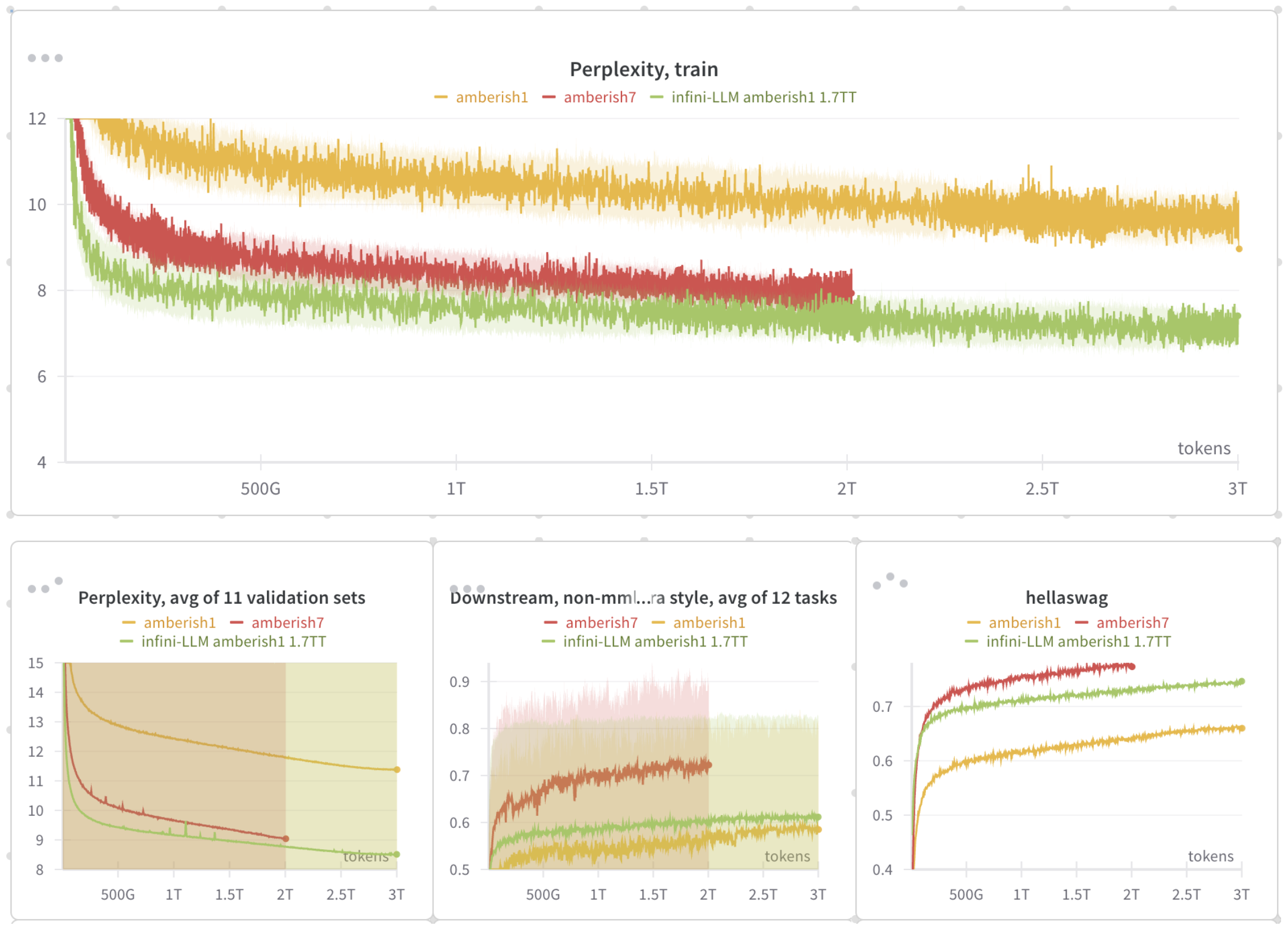

Training curves and in-loop evals of infini-LLM and baseline neural models. “amberish1”: neural-only OLMo-1B. “amberish7”: neural-only OLMo-7B. “infini-LLM amberish1 1.7TT”: an infini-LLM version of amberish1, with 1.7T-trillion-token n-gram datastore.

Training curves and in-loop evals of infini-LLM and baseline neural models. “amberish1”: neural-only OLMo-1B. “amberish7”: neural-only OLMo-7B. “infini-LLM amberish1 1.7TT”: an infini-LLM version of amberish1, with 1.7T-trillion-token n-gram datastore.

The perplexity (on both training and validation) of the 1B infini-LLM is hugely better than OLMo-1B, and even better than the 7B neural-only model. I also got some improvement on downstream tasks, with the most notable diff on HellaSwag (+10% accuracy from OLMo-1B, and almost close to the performance of OLMo-7B).

Passing on the torch

I don’t see myself having bandwidth to push on the infini-LLM project in the foreseeable future, and I’d love to pass on the torch to someone interested in exploring it. The initial results above are very encouraging. My code is available in this branch of the OLMo repo. Have fun!